SFI URBAN AND COMMUNITY FOREST SUSTAINABILITY STANDARD

LEAD THE WAY TO GREENER, HEALTHIER CITIES WITH THE SFI URBAN AND COMMUNITY FOREST SUSTAINABILITY STANDARD

- The world’s first forest standard for communities

- Promotes nature-based solutions and resilience to climate change

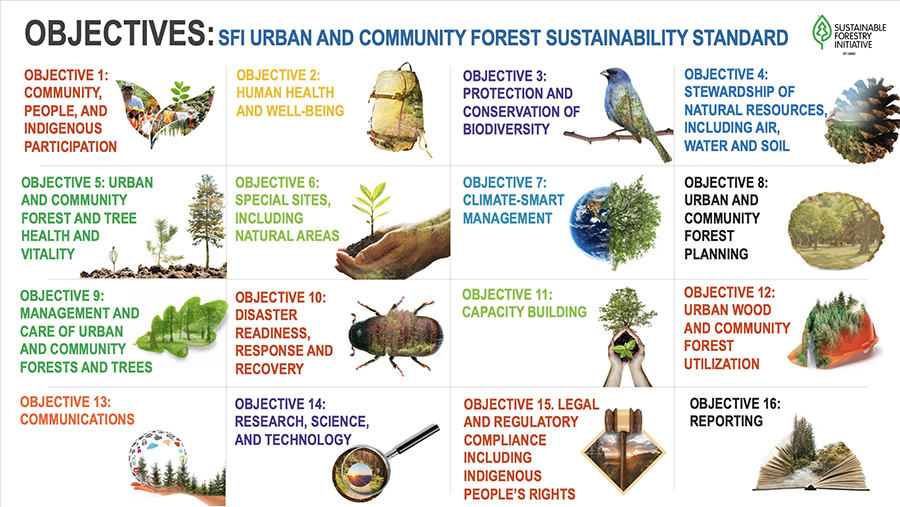

- 16 objectives for urban and community forest certification

- Third-party audits demonstrate effectiveness of management

- Applicable to cities and town of all sizes, anywhere in the world

- Perfect for corporate, hospital, and university campuses

- Helps maintain and enhance the many values of urban trees

Learn more about the thematic certification options:

-

- Community Well-Being and Human Health

- Environmental and Conservation Leadership

- Climate and Disaster Resilience

- Urban Forest Improvement

Download the SFI Urban and Community Forest Sustainability Standard here. (English | French | Spanish)

SCOPE

This standard is appropriate for organizations that own, manage, or are responsible for urban and/or community forests. These organizations can come from all facets of the urban and community forest sector, including, but not limited to: governmental organizations (i.e., municipalities, counties, states, provinces), non-governmental organizations, Indigenous Peoples, community groups, healthcare organizations, educational organizations, and corporate organizations.

FAQs

LEARN MORE

DID YOU KNOW

SUPPORTING FACTS AND RESOURCES

GUIDANCE FOR SFI URBAN & COMMUNITY FOREST SUSTAINABILITY STANDARD

SFI LAUNCHES PARTNERSHIP FOR URBAN AND COMMUNITY FORESTS

STANDARD DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

FACTS AND INFORMATION: SFI URBAN AND COMMUNITY FOREST SUSTAINABILITY STANDARD

SFI URBAN FOREST IMPROVEMENT GRANT PROGRAM

Full SFI 2022 Standards and Rules Documentation

Major Enhancements in the SFI 2022 Standards

Transition to the SFI 2022 Standards and Rules

Guidance For SFI Urban and Community Forest Sustainability Standard

Meagan Hanna

Director of Urban and Community Forestry for Canada

Tel: 613-800-3074

Michael Martini

Director of Urban and Community Forestry for US

Tel: 202-918-4701

Gregor Macintosh

Senior Director, Standards

Tel: 778-351-3358

Rachel Dierolf

Director, Data Analytics and Reporting

Tel: 613-274-0124

Paul Johnson

VP, Urban and Community Forestry and Career Pathways

Tel: 202-719-1389 ext 473